Etak Navigation

Sailing lessons for teams from native Micronesian experts

Where is New York City?

Depending on where and who you are, you might have a few different answers. If you’re standing on the Brooklyn Bridge, you’d be likely to point with your finger - there is New York City, it’s over there!

If New York City weren’t in view and you were far away from it, I might expect you to pull out a map on your phone and point to it. There is New York City, it’s that dot over there! It is almost second nature to us to use these two dimensional representations of space to find our way. I wrote about representations and different kinds of maps in more detail in The Map and The Territory, but today I want to chart a slightly different course.

In his rather wonderful 1995 book Cognition In The Wild, Cognitive Scientist, Anthropologist and Sailboat Racer (what a bio!) Ed Hutchins takes an interest in the ‘distributed cognition’ that takes place across a crew, a ship and their tools when navigating at sea.

As well describing his role as an on-board anthropologist of US Navy ships, he takes particular interest in the remarkable practices of Micronesian sailors who use traditional methods to navigate expertly between the Caroline Islands.

Your average Western sailor would be completely lost at sea without their compass, map, radar, clock, and radio. Navigating the sea is hard and Western sailors over the centuries have come up with many clever tools to help make it easier.

The Micronesian sailors on the other hand are able to successfully navigate huge swathes of the Pacific Ocean between dozens tiny, barely-visible islands using little more than their knowledge of their surroundings, a canoe, and some incredibly powerful culturally inherited - and entirely memorised - tools. It's an extraordinary feat, and one that has puzzled western students of their methods for decades.

In our lives it’s easy to confuse the tools and the cultural conventions that we use to represent the world for the world itself. For example when I sit in London and ask where New York City is, it’s highly likely that - like me - that you’ll unconsciously think of the familiar map of the USA and the little dot towards the right of it that represents New York City. New York City is not literally on that map, or on any map. New York City can only be found in, y’know, actual New York City. The map shows a representation of New York City which is useful to us in lots of ways.

Nonetheless New York city becomes the map of New York city in our minds. Our minds and our maps are intertwined in more ways than we can possibly know1. In the backs of our minds, we may believe that these kinds of maps are almost necessary for humans to get around.

Not so for the Micronesian sailors2. The way they think about space and place has no bird-eye two dimensional form. Instead they rely on a series of concepts and techniques that comprise etak navigation3. I’ll do my best to outline my understanding of etak navigation here, and then of course relate it back to finding our ways as teams in projects, products and other shared endeavours.

If I do a good job, I will fundamentally change the way you think about managing complex work and achieving lofty goals. No more, no less.

There are three etaks4 in etak navigation - the etak of stars, the etak of birds and the etak of sighting. I’ll explain them in turn.

Etak of Stars

The first thing to understand is that sailors from the region learn a deep and detailed knowledge of the sky and the star map that means they can get their bearings from stars alone. As the earth rotates throughout the day and the stars move across the sky, certain constellations will predictably rise from the same points in the eastern horizon and fall in the western horizon.

When the constellation of Orion for example rises on the horizon, it does so from a predictable point on the horizon, depending on the time of year. Once Orion has risen too high to be a good reference point, if you know what constellation is due to follow it you can orient yourself happily by this knowledge of the local star map. The arc that Orion and all it's successors follow is called a star paths. By knowing all the star paths for the night sky you can have a good sense of direction.

For the Micronesian sailors, their knowledge of the star map and the corresponding star paths is so good that they can find their orientation from even tiny patches of visible stars when the conditions are partially cloudy. This means that finding the right direction or ‘bearing’ is relatively trivial in the right conditions.

The next step is to hop in the canoe and set out on the known bearing from their point of departure to their destination. Knowing which direction to set off from island A to island B is helpful, but it's not precise enough to land them close enough to get the destination.

Instead the sailors need to know when they have gone far enough on the correct bearing before they should start to look out for signs of land fall. This is a tricky thing to do at sea without any way to measure distance, time or speed.

This is where the etak of star sighting comes in. The way the sailors conceptualise their journey is that the canoe is static, and as they travel the islands move around them along the horizon. This might seem farfetched, but for the sailors, it allows them to see their journey in terms of other observed phenomena outside of the canoe, rather than worrying about where they are.

If that feels like an overly ego-centric way of looking at the world, think about how we in the West view the Sun’s movement across the sky. We know from science lessons in school that it’s actually us sitting on the earth as earth rotates around its axis that makes it look like the sun is moving. Nonetheless it’s more practical usually for us to imagine that the sun is moving and we are watching it from a static position.

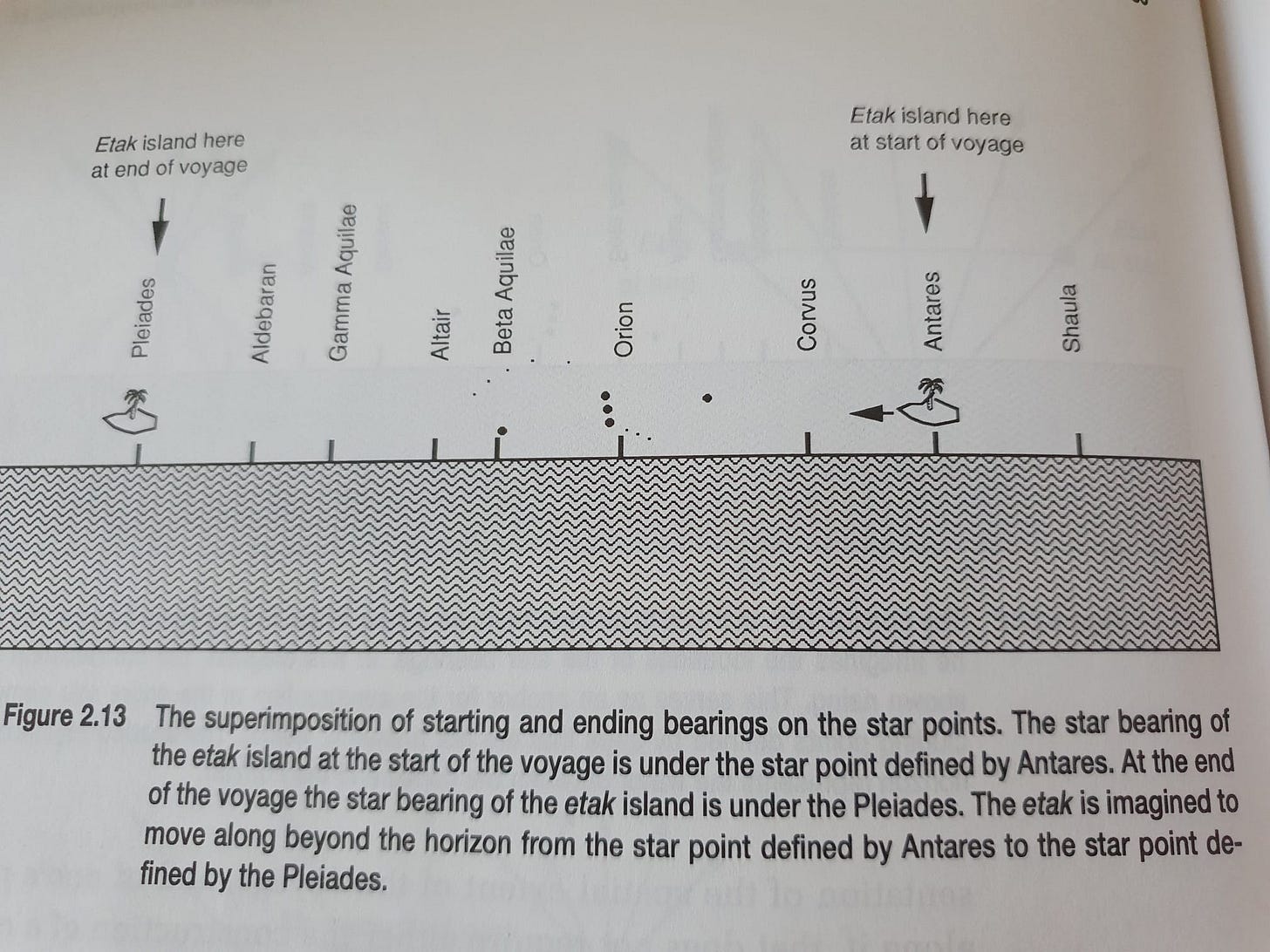

When Micronesian sailors travel from one island to another, say from the island of Poluwat to Guam, they will keep track of the movement of a ‘reference island’ - Chuuk - to show them where they are up to on their journey. Chuuk’s movement across the horizon is split into sections, also called etaks.

Throughout the journey, the sailors will keep track of where they expect Chuuk to be on the horizon. When Chuuk has finished moving from its expected starting point to its expected end point, the sailors have arrived in the vicinity of their destination and can start to expect the signs of land fall.

This is the ‘etak of star sighting’. A particularly wild and mind-blowing element of this method is that the sailor don’t actually need to be able to see Chuuk to use it as a reference island. In fact the anthropologists who have studied these methods have found that many of the reference islands don’t actually refer to physical ‘real’ islands!

To quote Thomas Gladwin who researched these methods in the 1970s:

When the navigator envisions in his mind’s eye that the reference island is passing under a particular star he notes that a certain number of segments have been completed and a certain proportion of the voyage has therefore been accomplished

The sailors are also so adept at knowing the speed of their boat from experience that they can keep track of where the reference island is, even in the dark, even at different speeds, and even if the reference island is a phantom island that doesn’t exist (other than in the cultural mythology of the method). You may find this animation helpful to get the intuition for it

The etaks (segments of the journey) that the etak (island) travels could be thought of as milestones along the journey which allow the navigator to keep track of where they are.

Etak of birds

When the sailors have entered the vicinity of their destination, they still need to do the finer navigation towards the destination island. For this they look out for the birds that they would expect to see, safe in the knowledge that certain birds will only be spotted within twenty miles or so to land.

Fishing birds will leave land at dawn and return at dusk, so if the sailors arrive at the expected point for the etak of birds during the night or after dawn, they drop sail and wait until dawn or dusk to give them more information. Failing to stop and take stock in favourable conditions could lead to the sailors overshooting their target.

Etak of Sighting

This is the most intuitive one. When they see the island, they sail towards it. I don’t think that one needs much more elaboration other than to remark that it sits alongside the etaks of stars and of birds. The etak of sighting is only available for a short section of the journey, and relies on the successful execution of the other etaks.

That’s interesting, so what?

Hopefully you’re still with me, and have a sense of the simple but ingenious intuitions behind this method of navigating. You’re probably chomping at the bit to find out why I’m including this hardcore esoterica in a publication about cognitive science and Intelligent Teams.

Allow me to flesh out the lessons as far as I see them. I’d be very keen to hear from you if you picked up something else from the description.

There are many ways to represent the same problem

The Micronesian sailors have a completely different worldview and set of conceptual tools to Western sailors. Both have conceptual frameworks for carrying out the complex computations involved in navigation which have been passed down through generations. For Western sailors these include chronometers, charts, alidades, GPSes and compasses, and for Micronesian sailors they have the rich understanding of the local environment, the star maps, their knowledge of the etak islands and their expected movements and everything else they memorise that supports etak navigation as described.

Whereas a Western sailor would represent their position on a chart, a Micronesian sailor would represent their position relative to the movement of reference islands and the stars - if they would even call what they are doing ‘representing their position’. More likely they would represent their position as ‘still in the canoe…’ and that the relevant information to help them navigate relates more to the real or helpfully imagined movements of reference islands around them.

Both methods bring strengths and weaknesses. Western methods can apply to help one sail the whole world, whereas etak navigation can only help you get around the region of the Caroline islands. Western tools export much of the knowledge and the experience into a physical tool which can be wielded (think of the centuries of discovery that are poured into every square centimeter of our maps), but can break, be lost or damaged.

Etak navigation on the other hand requires a full and lengthy immersion in the cultural setting of the sailors and to commit huge amounts of information to memory, but cannot be misplaced or damaged. One could throw the compass overboard, break the alidade or spill coffee on a chart. It’s much harder to lose or misplace a widely shared knowledge of the night sky distributed among the whole crew.

The representations of etak navigation allow navigation without any tools at all. The ways that Western sailors represent the problems involved in navigation mean that even a highly skilled sailor would be lost without their tools.

For both Western and Micronesian sailors, the artefacts and methods they use are culturally inherited. The tools are useful and meaningful because of the ways that the Micronesian and Western navigation cultures have developed these methods, taught the assumptions upon which they rely and there will be myriad other elements of human culture which make these tools useful.

Can we really talk about Western navigation without talking about the cultural construction of ‘the points on the compass’? Or Western conventions of mathematics? Imagining that a circle is split into 360 degrees and doing maths on it is a cultural artefact that has invaded our minds, it’s not a given that you need that artefact to get around. The Micronesian sailors do just fine without the conventions and inventions of Euclidian geometry. Better than Western sailors in many ways.

For us, representing New York primarily in two-dimensional, birds-eye map form totally makes sense and is an easy and well understood way to communicate with each other. To the Micronesians, representing a place from a bird’s eye perspective onto two dimensions is mind-boggling and unnecessary. It’s a leap of abstraction that means nothing and adds nothing to how they achieve their goals. In anthropological terms, one could say that these tools and representations are culturally contingent - their usefulness and existence relies hugely on the surrounding cultures in which they are used.

When we work in our teams and organisations, we often mistake the map for the territory, and we forget that there are many types of mapping and representations of different problems.

I’ve worked in places where the main currency for getting things done is to flag them on a ‘risk register’5. A risk register is a kind of representation of reality that some organisations use. It lists perceived future events and ranks them in terms of the likelihood of a bad thing happening and the impact of it happening as well as an accompanying plan of action. In a well oiled organisation, the most likely and highest impact risks should get the most attention and resources.

Risk registers only make sense in organisations that care about reducing risk. I don’t think many ‘move fast and break things’ startups are using them, but I know they are widespread in bigger, more bureaucratic and risk-averse organisations like governmental bodies. So a risk register is a culturally contingent tool, which only has power in highlighting risks to an organisation that cares about minimising risk. Within the microculture of a sexy unicorn startup, a risk register would carry no cache.

One could spend too much time in a big government agency and think that the only way any organisation could possible conceptualise the future is through the lens of risk and a risk register. When they encounter the zippy start-up who actively need to move fast and break things and for whom a missed opportunity is worse than a realised risk, they may have a similar jarring experience to the Western anthropologist trying to map etak navigation concepts onto their compasses and maps.

Consider the alternatives

As a Westerner, I know that I share many of the cultural starting points as a Western navigator, so if I learned how to sail it would be harder for me to see how many of the tools, beliefs and methods in Western sailing are culturally contingent. A fish isn’t aware of the fact that is swims in water, and humans aren’t automatically aware of the presence of our cultural scaffolding.

Culture is the lens through which we see the world, and just like the lenses of my glasses, I don’t see them unless I take them off to inspect them, or unless I see another glasses wearer.

So when we encounter a cultural phenomenon like etak navigation which relies on radically different starting points and outlooks than our own, this raises important questions. How many of the ways of knowing, the tools, and the beliefs that make up my every day experience do I take for granted but are actually mutable cultural artefacts? How much am I constrained and limited by cultural assumptions that I don’t even realise I’m using? What would the world look like if I could take off those metaphorical glasses and swap them for a different pair?

To be more concrete about the challenge, think about the example of hierarchy in an organisation. Some organisations run on hierarchy. It’s just a given that if my superior disagrees with my decision they can overrule me. The more important and urgent the decision, the more senior the person who signs it off should be.

This is a culturally contingent belief, and not all organisations run on it. There are plenty of organisations where full delegation and autonomy over certain elements of work are the norm. In fact the more important and urgent the decision, the more it should be delegated to those on the ground - think ‘Push authority to the information’ by David Marquet.

However when we spend enough time in hierarchical organisations to become acculturated to them we stop seeing the hierarchy as a feature which constrains and enables in equal measure. We just see it as normal and a given. This can be harmful, or it can be benign. We should at least be aware of it happening.

Multi-modal sensing

A Micronesian sailor will use many methods and observations about the world in their navigation. They will use stars, the speed of the boat, the state of the sea, the birds, the land, the time of day all in synchrony to get where they need to go. In fact the have such a good understanding of the sea and the locations of the reefs and underwater topological features that even the colour of the water helps them work out where they are.

It’s a kind of multi-modal sensing; understanding our place in the world through multiple corroborating sensory sources. If I smell smoke, see flames and hear beeping alarms, I’m much more likely to act as if there’s a fire than if I just hear a smoke alarm6. The Micronesian sailors combine their rich, multimodal knowledge of the world and their voyage into a coherent understanding that allows them to pull off their extraordinary navigation feats.

Often in projects we will look for a ‘single source of truth’ about project delivery or team health. Some projects can’t be delivered reasonably in small, two week iterations and they just need a sensible order of actions. In that case, it can be easy to ask ‘how far through this are we7?’ where the correct answer is a percentage.

In reality the team could think that they are 95% done with a project, but the last 5% takes as long as the first 95% because it happens to be more complicated, for reasons that could not have been predicted. How useful is the culturally transmitted belief that ‘progress can be represented in percentages’? It’s not no use, but it’s also clearly only a partial picture of progress.

Etak product delivery would involve bringing multiple corroborating and coherent sense-making tools towards answering a question like ‘when is this going to be done?'. One can look at the number of user stories, the perceived effort from the team, the perceived complexity of the remaining work. One could normalise a big delivery against another similar-sized-looking projects as a rough baseline. Sophisticated practitioners might use methods such as story points, velocity, or flow metrics to furnish their predictions. Unsophisticated practitioners will also use the same methods and it can be hard to know if you’re in the former category or the latter. I’ll save that for a future post.

That’s all for this edition of Intelligent Teams. If you have thoughts, share them! Comment on this post or share it with your network. Even better - subscribe and encourage others to

If you want to find out what else I’m up to, you can subscribe to Daniel’s Community of Practice. You’ll get a free weekly Start The Week email with 3 points to ponder and set you up for a week of leading empowered agile teams.

I’ll also be running another edition of Scripture@Work with my friend Tobias Mayer on Thursday evening (UK time). We study a passage from scripture and - as a Jew and Christian who both work with teams - we host a conversation about how these texts can help us understand teams, leadership, organisations and more. That’s Thursday 16th Jan.

Until next time.

This kind of idea is part of the Extended Mind hypothesis put forward by Andy Clark and Dave Chalmers.

Much of this article will be about some of the - erm - drier elements of navigation. I’m not going to pretend to be any kind of expert or even tourist in Micronesian culture or history. I’m taking something fascinating I found in a book to share. For a richer, alive window into this world, check out this film by Dakota Camacho elevating indigenous artists and their engagement with etak

Annoyingly there is a kind of old GPS named after Etak so if you Google ‘etak navigation’ that’s the main thing that comes up. This does however present me with the opportunity to be nearly certain this will be the first you’re hearing of this idea. If you know more about etak navigation than me please do reach out I’d love to chat, nerd-on-nerd.

‘Etak’ refers to many things so I'll ask you to go with the flow on what is and is not called an etak. According to the contributors to Wikipedia it means ‘refuge’. The fact that an etak refers to a unit of measurement, an island, a whole method and subsections of a method confused the aforementioned western anthropologists who were determined to make the term fit to their worldview, which I think is pretty funny

I’m not going to take a judgement on whether risk registers are a good idea or not or to be pro or anti them. My point here is that they are a cultural artefact just like a map of New York City and that it’s helpful to be aware of that.

This is not a prescription for action. If you hear a smoke alarm, please act as if there’s a fire. Intelligent Teams accepts no liability for you not paying attention to smoke alarms.

This should probably be ‘they’. This question is almost exclusively asked by people outside the team who are worrying, sometimes for good reason sometimes not.

thanks for sharing!