Communicate more clearly - going deeper with speech acts

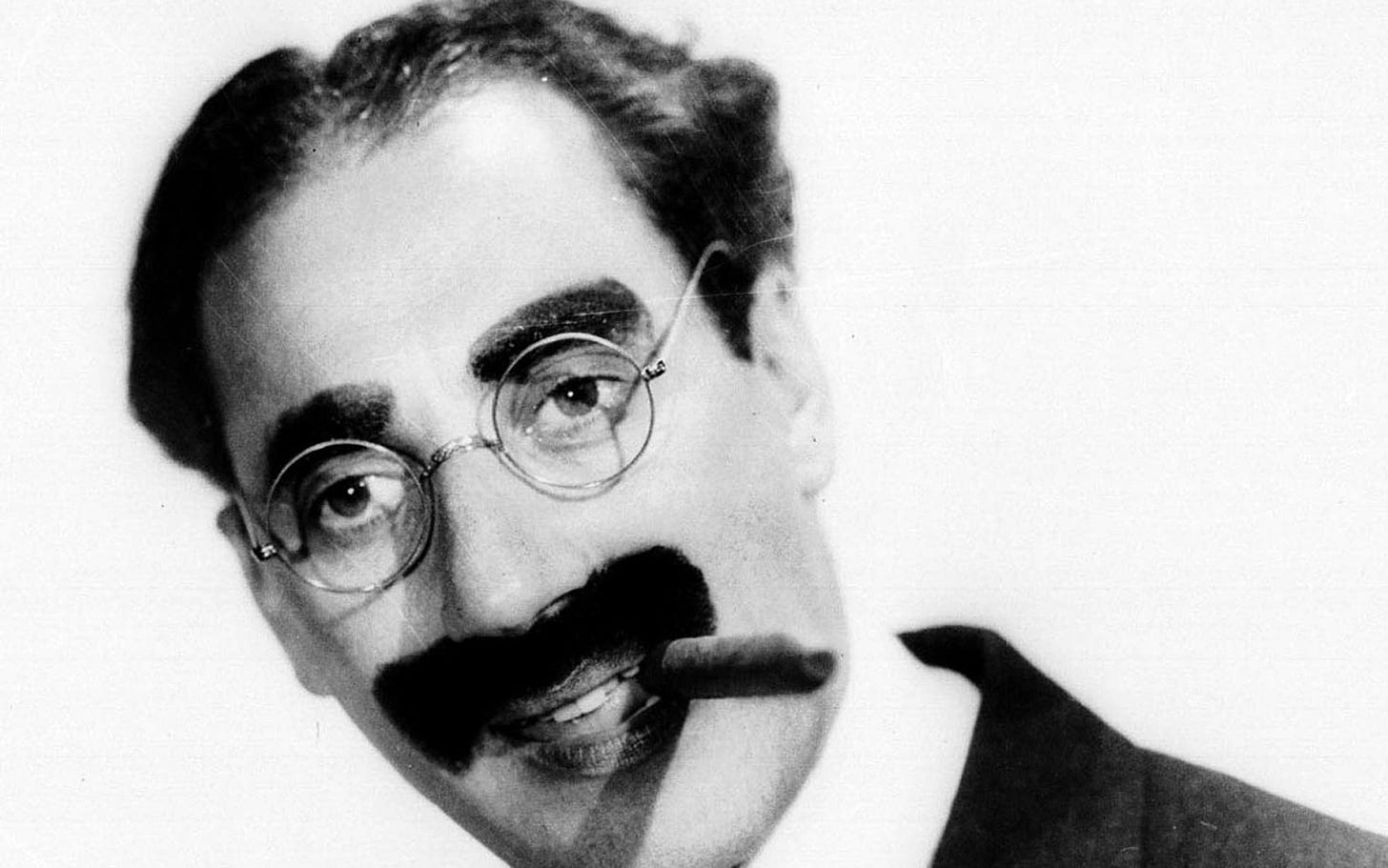

“One morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got in my pyjamas I dunno” Groucho Marx

The only thing you can guarantee about communication is that at some point, someone will misunderstand you. Most of the time this is harmless, or leveraged for humour as Groucho masterfully demonstrated above. Other times it can be catastrophic.

Let me share a cautionary tale. On 23rd September 1999 NASA lost contact with the Mars Climate Orbiter. They had spent $125 million to send the craft to survey Mars from orbit. Alas, after losing contact they discovered it had crashed into the surface of the planet. The culprit? A miscommunication between Lockheed Martin Astronautics and Jet Propulsion Laboratories - two suppliers who had built the craft. Whereas JPL had been using metric units, Lockheed Martin were using imperial units.

This led to a very expensive lesson - conversations are full of assumptions, and if we don’t communicate what we mean effectively, it can lead to unintended consequences.

In my work building intelligent agile teams I have roughly two main focusses. I help teams to:

Have better plans

Execute their plans better

In both of these focusses, it’s incredibly important that the team members understand each other. When it comes to having better plans, an intelligent team is able to make sure of all the knowledge and information that sits among the team members.

To execute their plans better the teams must be able to hand off information to each other effectively, to make micro-decisions about how to proceed and be able to ask each other for help. You know this isn’t happening if you have a team that are confused about their plans, need to be told what to do next by a central authoritative person (like a project manager or team leader), or work in an uncoordinated way (one team sending measurements in metric, another in imperial, for example).

Here are a few examples of when communication can go wrong in a team. Imagine:

the team’s product manager makes a request but the team treat it like an order and slavishly carry it out with great suffering

the team make a request of the manager but it is understood as an ultimatum or a threat

one team member shares an opinion that the work will be done by Friday, and that is heard as a promise that it will be done by Friday. The work isn’t done by Friday - heads roll

the product manager decides that feature X is the most important thing, but the team think that this is as an opinion rather than a decision and work on feature Y instead

I’m sure you can think of a million other examples from your own lives. As people who are interested in building high performing, intelligent teams, how can we help our teams communicate better?

To answer this, I want to turn back to the cognitive science of communication. Let’s look at Speech Acts.

In my last post I introduced JL Austin’s three speech acts - locutionary (the actual speech), illocutionary (the intent or meaning), and the perlocutionary (the desired result of the illocution).

So if someone turns to their date as the evening draws to a close and says ‘would you like to come up and see my stamp collection?’ we could do the following analysis:

Locutionary act (what is said): ‘‘would you like to come up and see my stamp collection?’’

Illocutionary act (what is intended or meant): “I would like to invite you to my home for a romantic liaison”

Perlocutionary act (what is desired as a result of the illocution): The hearer agrees to come back to the speaker’s home for a romantic liaison.

We looked at how this could apply to workplace feedback, but this is just the beginning. Building on that work, I want to introduce John Searle’s classification of illocutionary acts.

Searle’s five Illocutionary Acts

Like all good linguists, philosopher John Searle was interested in understanding which kinds of illocutionary acts happen in our speech. What is it that fundamentally distinguishes a request from an invitation from a statement of intent or a promise?

In an influential 1976 paper he classified 5 different types of illocutionary act. As a linguist, Searle was interested in taxonomies and finding philosophically watertight definitions for different types of speech act. This is a useful thing to do if you’re trailblazing the frontiers of the philosophy of language. If we want to programme our AIs to speak, then it’s sensible to get really nerdy about the mechanics of speech and meaning.

Don’t worry - this post won’t be as rigorous as that. My aim is to introduce thought-provoking ideas that give us tools and approaches to building intelligent teams. So I want to offer some basic ideas, and suggest some avenues for how to bring them into your workplace. For even further nerdery, read this and this.

Searle describes three components that make up the different illocutionary acts

The Point/Purpose of the act: When I make a speech act I want the hearer to do something. If my speech act is to describe my holiday I want the hearer to understand what happened on my holiday and maybe feel jealous. If I request to see your holiday photos the point is for the hearer to show the speaker their holiday photos. All speech acts have a point or a purpose.

Direction of fit: Some speech acts are about getting the world to conform to my words, for example if I ask my girlfriend to close the window, I want the world (the window) to conform to my request (my word). Searle calls this world to word direction of fit. Other speech acts try to get the words to conform to what is true in the world. If my girlfriend asserts that the window is already closed, she is trying to get her words (the assertion) to conform to what is true in the world (the state of the door). Searle calls this word to world direction of fit.

Differences in psychological states: Speech acts tend to express the psychological state of the speaker. For example a request expresses a desire that the hearer does what the speaker wants. A promise expresses the intention of the speaker. A description expresses a belief.

If we jumble these up in their different combinations we get Searle’s five Illocutionary acts - Representatives, Directives, Expressives, Commissives and Declarations. We’ll go through each one in its turn. Stay with me it’s good.

I’m going to describe each act and give some examples and show how it relates to these three components. Then I’ll discuss briefly how we can use these illocutionary acts better at work. I’ll even share some practical tools because I’m good to you like that.

Representatives

Structure:

I (the speaker) wish to represent something (a proposition) that I believe to be true about the world.

Examples:

Assertions: “It is raining outside”

Testimonies: “I swear on this holy bible that I saw Jimmy with his hands in the cookie jar”

Hypotheses: “I reckon that riding that unicycle with a tray full of hot bean soup will lead to you getting burnt”

Point/Purpose: the speaker commits to a certain proposition being true

Direction of Fit: word to world

Psychological State: The speaker expresses a belief that a proposition is true

At work you might see representatives in feedback conversations “I think that was a good session, good job Michelle” or in team meetings where people share information with each other - “the database is working, I swear”.

In a healthy team, Representatives are clear in the scope of what they are trying to achieve. So if two people are disagreeing about something, it is clear that they are both saying ‘I believe x’ to be true or false. In a healthy team, disagreement about Representatives can be resolved by going and finding out what is true.

Let’s say Raj thinks that the customer will *love* our new ‘find a local pet shop’ button, and Nicole thinks they will hate it, we have a disagreement about facts. We can resolve this by setting up an experiment to test whether Raj or Nicole is right and then we can move on.

Alternatively we could agree that it doesn’t actually matter who is right because we aren’t ever going to work on that product because we are a high street bank. Then we can let Raj and Nicole happily disagree and move on with our lives.

In dysfunctional settings, Representatives turn into attacks on each others’ character. If you don’t agree with my assertion, then maybe you don’t trust me. You don’t trust me because this place is toxic and I’m outta here.

A leader’s job is to help the team clarify which Representative speech acts are taking place, how we can resolve conflicts like Raj and Nicole’s and use them to make good decisions and plans. Try asking clarifying questions like “how do you know that is true?” or “Nicole, what makes you think that?”. State the conflict and then ask “How can we find out which of these assertions is true?”.

Directives

Structure

I (speaker) have a desire for you (the hearer) to do something (action)

Examples

Requests: “Please could you present my slides at the next team meeting”

Invitations: “Please come to my birthday party”

Orders: “Drop down and give me 20 pushups”

Begging: “For the love of God please stop cracking you knuckles in the office”

Questions: “What time is it?” (questions are trying to direct the hearer to give an answer)

Point/Purpose: For the hearer to do what the speaker wants

Direction of fit: World to word

Psychological state: The speaker’s desire or will for the hearer to do something

I would argue that Directives are the most misunderstood speech acts at work. What sounds like a request could actually be a non-negotiable order, or vice versa. Directives are things that in principle you can say ‘no’ to. How much healthier would our organisations be if people said no to more stuff instead of thinking that every request was a direct order.

It should go like this:

Speaker: “do you have capacity at the moment? I need some help with my spreadsheet”

Hearer: “no, I’m actually busy with something higher priority at the moment. Sorry.”

Speaker: “cool, I’ll ask someone else”

This should be true regardless of power structure. If your manager asks you for something after reading this article, I would hope that they would clarify whether they are making a request, a demand, an order, a plea or an invitation. I don’t mind if my manager gives me an ‘order’ (depending on the order), I just want clarity about whether this is the kind of thing I can actually say no to. In intelligent teams these kind of hard orders are few and far between.

A few years ago I attended an activity on consent at a festival. My friend who was running it asked everyone to walk around a circle, catch eyes with someone and say ‘no’, then keep going. After a few minutes the instruction changed to say ‘yes’. Then for the third round you could choose whether to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The yes and the no didn’t mean anything, there was no request. Nonetheless it was interesting to feel how it felt to say even a meaningless ‘no’ to someone. I remember noticing that I felt like I would hurt their feelings, or leave them feeling rejected.

If that’s the case with meaningless ‘no’s, no wonder it can be difficult to say no to someone who is actually asking you for something.

Try an exercise like this with your team. Teach them the different types of Directives. Be clear with which kind of Directive you are giving, or being given.

Commissives (from the word commit)

Structure

I (the speaker) express to doing a future action

Examples

Promises: “I will come to your party”

Threats: “If you keep making terrible puns I will leave this room”

Guarantees: “I’ll never make another terrible pun again in my life”

Point/Purpose: The speaker expresses an intention to perform an action

Direction of fit: world to word (I want my actions to fit this commitment)

Psychological state: The speaker reveals their intention

Commissives at work are often promises of when something will be done, or about behaviour. If I am given feedback I think about whether these is a commissive that I should make in response. So if someone tells me that my style of constantly interrupting them in meetings makes them feel unimportant, I can make the promise that I’ll try not to do that any more.

Commissives can be confused with Representatives. For example if a team says ‘I reckon this work will be done by Friday’, they might be making a Representative - ‘we believe that this work will probably be done by Friday’. The hearer could think that they are making a commissive ‘we promise that this will be done by Friday’. On Friday that miscommunication could lead to conflict.

In most of our work we are dealing with complex problems, which means that we cannot know for a fact when something will be done. I work with software teams where even simple changes to the code can cause significant unintended consequences. I try to steer my teams away from making promises about when the work will be done - Commissives - and move more towards making informed predictions and forecasts - Representatives. Why make promises about things that are not in your control?

For more about forecasting with agile teams, take a look at Dan Vacanti’s work on forecasting metrics.

Expressives

Structure

I (speaker) express a psychological state regarding you (hearer).

Examples

Congratulations: “Well done on your making of a delicious cake”

Gratitude: “Thank you for transferring me that bitcoin”

Apologies: “I’m sorry for spilling wine on your face”

Point/Purpose: The speaker expresses a psychological state in regards to something about the hearer

Direction of fit: Searle argues this doesn’t apply here! The ‘world’ state has already happened and neither word nor world are trying to be conformed to the other

Psychological state: The speaker can have various psychological states about something that the hearer did

Expressives at work come up with feedback ‘I was hurt that you made fun of me in that meeting’, and apologies ‘I’m sorry for making fun of you in that meeting’. When I teach people how to give effective feedback, I teach people to use the Expressive when they want to highlight the consequence of a particular behaviour.

The power of a well-placed congratulations shouldn’t be underestimated, and thanking people who have helped you along the way can help teams feel appreciated.

However, something that annoys me personally is when management ‘thanks’ a team for doing a piece of work. I think it cements the idea that management are the real customers and when a team does something cool the real purpose was to make their leaders look good. It’s disempowering for the team.

I try to congratulate and say ‘well done’, rather than to thank teams publicly (unless they have done something that actually helps me). Reasonable minds may differ on this point.

Declarations

Structure

I (speaker) declare the following (proposition) to be true

Examples

Naming: “I name this ship the Mary Rose”

Decision making: “It’s decided, we’re going with plan A”

Dismissing: “You’re fired”

Marrying: “I pronounce you husband and wife”

Point/Purpose: The speaker makes something true by declaring it

Direction of fit: Both world to word and word to world - by saying the Declaration the world conforms to the word, but also the other way around. Another slightly weird one.

Psychological state: Doesn’t apply here. When I announce someone as husband and wife, assuming I’m authorised to do so and in the proper context it doesn’t matter whether I mean it or not, or whether I want it or not.

Declarations at work might appear in team meetings as group or manager decisions. If you ask someone for a prioritisation call, they might give you an answer and in doing so they are declaring the priority of that item.

Team decisions are another key one - few things are worse than spending hours debating a topic in a group only to come out not knowing the decision or the outcome. Good leaders will be able to make decisions with the right amount of inclusivity (check out Delegation Poker for more detail on how to do this). Sometimes it’s right for a decision to be made democratically, sometimes it should be up to a leader to decide. In either case Declarations should be clear.

One of the points of facilitating meetings well is to make sure that people understand what is being argued and agreed upon. I often use the ‘clarifying question’ technique. When someone makes a proposal, we spend time as a team clarifying what the proposal means, and not trying to attack or support it. That way when the team accepts of rejects the proposal, they know what they are signing up for. Intelligent teams understand what Declarations have been made.

If we learn how to distinguish between these types of speech acts in our work we will create more aligned, well oiled, and intelligent teams. Good teams will understand which kinds of speech acts are taking place. Intelligent teams will go further and build their understanding of different speech acts into the system of how they work. It will pervade the way their conversations take place and the way they make decisions at every level.

Thanks for reading this post about speech acts. Please do subscribe if this is something you want more of.

However the most useful thing you can do for this substack is to submit some feedback. It will take approximately 1 minute and help me immensely.

The next most important thing you can do is to upgrade your subscription to a paid one. You’ll get everything that you get with your free subscription, but with the added benefit of helping me afford my rent.

Next time we’ll delve into Metaphor to wrap up this mini series on linguistics. Wrap up - thats a metaphor! See you next time.